About

Tanya Datta is a storyteller

Whether her raw materials lie in the hard truths she unearths as an investigative journalist or the soft clay of her own imagination as a writer of fiction, she loves nothing more than to shape them into compelling narratives for an audience.

Always mindful of what separates the two, Tanya’s journalism and literary work inevitably colour each other stylistically, resulting in a distinctive voice across both her factual and fictional output.

Tanya is attracted to stories that mostly unfold under the radar. She has a good antenna for anything unusual or unjust, can ferret out long-buried details and is compulsively interested in people and history.

The story so far…

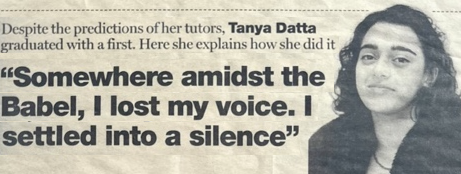

Tanya attended her local secondary school, Fortismere, in north London, before going on to Oxford University where she graduated with a First in English Literature. She started out in journalism as Women’s Editor on the India Mail, a weekly newspaper aimed at the UK’s diaspora Indian community.

About

Tanya Datta is a storyteller

Whether her raw materials lie in the hard truths she unearths as an investigative journalist or the soft clay of her own imagination as a writer of fiction, she loves nothing more than to shape them into compelling narratives for an audience.

Always mindful of what separates the two, Tanya’s journalism and literary work inevitably colour each other stylistically, resulting in a distinctive voice across both her factual and fictional output.

Tanya is attracted to stories that mostly unfold under the radar. She has a good antenna for anything unusual or unjust, can ferret out long-buried details and is compulsively interested in people and history.

The story so far…

Tanya attended her local secondary school, Fortismere, in north London, before going on to Oxford University where she graduated with a First in English Literature. She started out in journalism as Women’s Editor on the India Mail, a weekly newspaper aimed at the UK’s diaspora Indian community.

After being selected for a Scott Trust Bursary, she went on to study newspaper journalism at City University and was subsequently offered a place on both the BBC Regional News Trainee Scheme and the ITN News Trainee Scheme. She opted for the latter where she trained further in broadcast journalism before ironically taking on a staff role at the BBC.

As a current affairs journalist, Tanya has reported across both radio and television on BBC Radio 4, the World Service, BBC2, Channel 4 and has presented debates on YouTube more recently. She has written for several print outlets and produced multiple radio documentaries for Radio 4, Radio 3 and Five Live. Over the years, some of her hard-hitting investigations have attracted huge publicity and, occasionally, controversy.

Her path as a writer is more serpentine. Tanya has written fiction ever since childhood but her writing only emerged into the open after she completed a MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck College. She recently stumbled across one of her short stories on a study website for Danish high school students and discovered it had been used as an exam set text in Denmark! Currently, she is in the final stages of completing her first novel.

Tanya is a Londoner with roots in India.

About

Tanya Datta is a storyteller

Whether her raw materials lie in the hard truths she unearths as an investigative journalist or the soft clay of her own imagination as a writer of fiction, she loves nothing more than to shape them into compelling narratives for an audience.

Always mindful of what separates the two, Tanya’s journalism and literary work inevitably colour each other stylistically, resulting in a distinctive voice across both her factual and fictional output.

Tanya is attracted to stories that mostly unfold under the radar. She has a good antenna for anything unusual or unjust, can ferret out long-buried details and is compulsively interested in people and history.

The story so far…

Tanya attended her local secondary school, Fortismere, in north London, before going on to Oxford University where she graduated with a First in English Literature. She started out in journalism as Women’s Editor on the India Mail, a weekly newspaper aimed at the UK’s diaspora Indian community.

After being selected for a Scott Trust Bursary, she went on to study newspaper journalism at City University and was subsequently offered a place on both the BBC Regional News Trainee Scheme and the ITN News Trainee Scheme. She opted for the latter where she trained further in broadcast journalism before ironically taking on a staff role at the BBC.

As a current affairs journalist, Tanya has reported across both radio and television on BBC Radio 4, the World Service, BBC2, Channel 4 and has presented debates on YouTube more recently. She has written for several print outlets and produced multiple radio documentaries for Radio 4, Radio 3 and Five Live. Over the years, some of her hard-hitting investigations have attracted huge publicity and, occasionally, controversy.

Her path as a writer is more serpentine. Tanya has written fiction ever since childhood but her writing only emerged into the open after she completed a MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck College. She recently stumbled across one of her short stories on a study website for Danish high school students and discovered it had been used as an exam set text in Denmark! Currently, she is in the final stages of completing her first novel.

Tanya is a Londoner with roots in India.

After being selected for a Scott Trust Bursary, she went on to study newspaper journalism at City University and was subsequently offered a place on both the BBC Regional News Trainee Scheme and the ITN News Trainee Scheme. She opted for the latter where she trained further in broadcast journalism before ironically taking on a staff role at the BBC.

As a current affairs journalist, Tanya has reported across both radio and television on BBC Radio 4, the World Service, BBC2, Channel 4 and has presented debates on YouTube more recently. She has written for several print outlets and produced multiple radio documentaries for Radio 4, Radio 3 and Five Live. Over the years, some of her hard-hitting investigations have attracted huge publicity and, occasionally, controversy.

Her path as a writer is more serpentine. Tanya has written fiction ever since childhood but her writing only emerged into the open after she completed a MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck College. She recently stumbled across one of her short stories on a study website for Danish high school students and discovered it had been used as an exam set text in Denmark! Currently, she is in the final stages of completing her first novel.

Tanya is a Londoner with roots in India.

Read

Reviews

This was a gruesomely gripping programme that raised all manner of perplexing issues.

In this frank and jaw-dropping documentary, presenter Tanya Datta explores what happens when Asians and blacks fall in love… Thought-provoking stuff.

Tanya Datta reports from Paraguay on the unlikely curse of GM soya… her unsettling report reveals that the beautiful Paraguayan rural scenery is now a backdrop to a desperate and sometimes violent conflict…

The chatter of children, the squawk of gulls, the roar of waves, the descent of rain on sometimes parched earth, giggles, clangs, chimes, chants, the clash of cymbals, the whirr of insects…the sound is a memorial to those who are gone, a tribute to the spirit of the survivors and a way of connecting us and them…There is great hope in all of this and also intense sadness…

“…reporter Tanya Datta did her job properly and went far beneath the surface of magic tricks and gaudy tat… An hour wasn’t enough to do the subject justice, and for once I was left wanting more.

“Tanya Datta’s report on the Indian guru, Sai Baba… provided an alarming illustration of just how willing people are to be conned.”

“Presented by the alluringly eloquent Tanya Datta, this was a documentary full of surprises…”

Reporter Tanya Datta finds a landscape blighted by intimidation and violence…. A direct, devastating report..

Tanya Datta is the BBC journalist who made Radio 4’s remarkable Tsunami Audio Memorial last December. Today she explores a much less discussed topic: the ‘deep and sometimes ugly tensions’ between Britain’s two largest ethnic minorities, blacks and Asians… She has gained some extraordinarily candid interviews about romance and racial hierarchy: a real achievement and a gripping listen.

This was a gruesomely gripping programme that raised all manner of perplexing issues.

In this frank and jaw-dropping documentary, presenter Tanya Datta explores what happens when Asians and blacks fall in love… Thought-provoking stuff.

Tanya Datta reports from Paraguay on the unlikely curse of GM soya… her unsettling report reveals that the beautiful Paraguayan rural scenery is now a backdrop to a desperate and sometimes violent conflict…

The chatter of children, the squawk of gulls, the roar of waves, the descent of rain on sometimes parched earth, giggles, clangs, chimes, chants, the clash of cymbals, the whirr of insects…the sound is a memorial to those who are gone, a tribute to the spirit of the survivors and a way of connecting us and them…There is great hope in all of this and also intense sadness…

“…reporter Tanya Datta did her job properly and went far beneath the surface of magic tricks and gaudy tat… An hour wasn’t enough to do the subject justice, and for once I was left wanting more.

“Tanya Datta’s report on the Indian guru, Sai Baba… provided an alarming illustration of just how willing people are to be conned.”

“Presented by the alluringly eloquent Tanya Datta, this was a documentary full of surprises…”

Reporter Tanya Datta finds a landscape blighted by intimidation and violence…. A direct, devastating report..

Tanya Datta is the BBC journalist who made Radio 4’s remarkable Tsunami Audio Memorial last December. Today she explores a much less discussed topic: the ‘deep and sometimes ugly tensions’ between Britain’s two largest ethnic minorities, blacks and Asians… She has gained some extraordinarily candid interviews about romance and racial hierarchy: a real achievement and a gripping listen.

This was a gruesomely gripping programme that raised all manner of perplexing issues.

Watch

BBC2 This World – Secret Swami

Investigating claims of sexual abuse and murder against India’s most powerful godman, Sai Baba (Available on YouTube in seven parts)

Ch4 Unreported World – Painful Harvest

Examining the worrying impact of GM soya farming in Paraguay. This film was short-listed for the One World Environment Award (Available via online library Thought Maybe)

YouTube – The Five Masters

Discussing the social business entrepreneur Phillip Ullmann’s radical proposals for creating a fairer society in contemporary Britain (Available on YouTube in four parts)

YouTube – The Five Masters

A conversation with social business entrepreneur Phillip Ullmann and Labour peer Lord Glasman on how a covenantal approach would benefit society (Available on YouTube in five parts)

Contact

Stuff

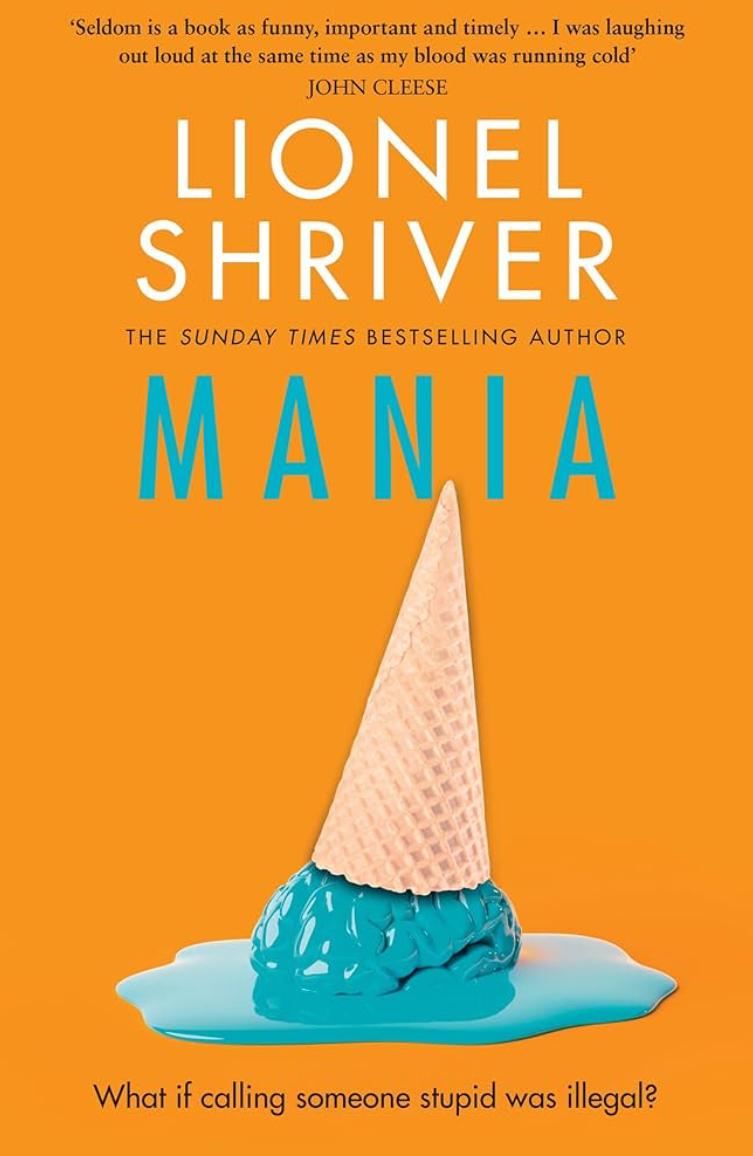

I am delighted to be conversing with author Lionel Shriver for the paperback launch of her thought-provoking novel, Mania. Please join us on Friday 28th March at the Odney Club in Cookham. Doors open from 6.30pm. More details on how to get a ticket here- https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/an-evening-with-lionel-shriver-in-conversation-with-tanya-datta-tickets-1127513536339?utm_experiment=test_share_listing&aff=ebdsshios

The Tom Grass ‘Spirit of Adventure’ Literary Prize is a writing prize dedicated to celebrating the spirit of my friend Tom Grass, a multi-talented writer, avid reader and fearless traveller. I am honoured to be one of the six judges in its inaugural year and would like to encourage anyone around the world writing in English and aged 25 and over to enter. You can get the competition details here: https://www.tomgrassprize.com/

It was a pleasure to chair the Thames and Hudson book launch for the award-winning architect Thomas Hetherwick. His updated and revised 600 page opus – Making – is extraordinary and is a personal account of key projects from the 30 year career of this visionary designer, going into many of the challenges he faced along the way and how he overcame them. For more details on how to get the book: https://thamesandhudson.com/thomas-heatherwick-making-9780500297162

I have been walking.

Although walking seems too tame a word for the feverish grief-fuelled tramping I have found myself undertaking since the middle of July.

Perhaps a truer description would be that I have felt compelled to move and keep moving in the aftermath of a severe shock.

I lost my brother last month; admittedly, not a brother by blood but a close friend who wanted the the role. I was not expecting it. Even though he was only a few years into remission; even though he appeared frail the last time I saw him at his birthday gathering in May; even though his final text to his “little sister” on my own birthday in June was suffused with enough love and affection to last for an eternity, I suspected nothing. And so, the cut was deep and treacherous.

Within a day of receiving the news, I was dragging myself along the tranquil boulevards that flank the main road on which I live, past the fat suburban semis that hide there, past their disturbingly perfect front gardens; a wounded animal on the loose.

I felt half-crazed with sorrow. Haunted by my infinite stupidity. How could I call myself an investigative journalist when I had failed to see the crime playing out right in front of me? How could I have been so unforgivably blind?

And so I stumbled on, day after day, churning with regret and memories.

Friendship At First Sight

I first encountered Sumeet back in 1995. I had just been hired as the Women’s Editor of the India Mail, a weekly newspaper aimed at the UK’s diaspora Indian community that was based in Wembley. It was to be my first job in journalism and despite the pittance I would be paid and the grubbiness of the newsroom where I would work, I felt euphoric. And yet, my most crystalline memory of that day was not me being hired, but the jaw-dropping moment that the paper’s chief reporter was introduced to me.

Sumeet was small and slender and wore a white shirt topped off with an eye-catching silk neckerchief that highlighted his beautiful face. But it wasn’t how he looked that caused me to stare, it was how he sounded. I had never heard an Indian talk like that before. His voice evoked the characters in a PG Wodehouse novel. It was a mixture of Professor Higgins and Shere Khan. In other words, the most plummy, languorously articulated RP (Received Pronunciation for those who don’t know) imaginable.

That rich sardonic drawl when employed in tandem with his rapier-sharp wit could skewer any subject of his choosing. So when Sumeet welcomed me to the newspaper, taking his time to elongate every vowel, I was laughing before I could even work out why. I decided on the spot that I had to have him as my friend. And luckily for me, he concurred.

In the big details of our lives, Sumeet and I were like chalk and cheese. He was from an upper-class Gujurati family based in Delhi while I hailed from a middle-class Bengali family originating in Calcutta. His parents leaned traditional and conservative whereas my mother was a divorcée defiantly raising me alone. He had been dispatched to India and the UK’s top boarding schools, while I had been kept close and sent to the local comprehensive.

But none of that ever mattered, because right from the off Sumeet and I simply delighted in our similarities. We were both small, both brown, both highly social, both super observant, both deeply irreverent, both ridiculously juvenile, and both only children (although by now I had a baby half-sister in the wings) who absolutely adored our mothers.

Also incontrovertible – we loved to make the other laugh.

Siblings By Choice

And believe me, there was a lot to laugh about in our workplace. Such as the hole in the newsroom floor that led directly to the Sari Emporium below. Such as the weeks we had to survive on petty cash handouts when our salaries failed to materialise from India. Such as the four strong editorial team being forced to write articles on antique typewriters because the newsroom’s only PC had been cornered by the Managing Director’s PA.

It didn’t take me very long to discover that the India Mail was an embarrassingly amateur and chronically under-funded newspaper that somehow pulled off the astonishing feat of being published every week. It was also through its existential fight for survival that Sumeet and I gained such a crucial grounding in journalism.

Sure, there were plenty of days when we essentially rewrote copy from Indian press agencies to fill up the pages. Equally, though, there were others when Sumeet and I worked hard to generate original, ground-breaking articles, some of which occasionally attracted the attention of the national press. It wasn’t that unusual for either one of us to be called in to mainstream newsrooms and live studios to comment on stories that had originated from us. The mid-90s were peak political correctness and media organisations were slowly starting to tackle their diversity problem, albeit in the most superficial way. At most of the press events, it was common for Sumeet and me to be the sole journalists of colour.

Working alongside him made me realise that it wasn’t just his voice that made Sumeet a one-off. It was everything. His piercing intelligence, his big soppy heart, his comic genius and his deep affection for a diverse circle of friends. Part of his uniqueness was undoubtedly his infatuation with the TV series, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and his irrepressible desire to sing the full repertoire of the hit musical Jesus Christ Superstar even when begged to stop.

A few months after becoming friends, Sumeet suggested we mark Raksha Bandhan where sisters tie a hand-made bangle known as a rakhi around their brothers’ wrists as a token of their everlasting love; and brothers, in return, promise their sisters eternal protection. I’d always thought it an iffy custom myself. Besides, Sumeet was small – what could he protect me from? But we went ahead and I tied my bangle on him and he made his promises to me, and from that point on, our bond deepened without us even realising it.

I can never forget my new self-anointed bhai waggling his finger at me as we stood on the rundown Ealing Road, the garish rakhi I’d just made him glittering on his wrist. “Now be careful not to get into a fight with anyone too big!”

Roaming and Remembering

The memory plucks me from the mid-90s and slams me back into 2023 leaving me laughing out loud on this leafy, well-to-do street then inevitably weeping as reality hits anew. I lean against a garden wall, once again breathless with disbelief. Vivid blue agapanthus blooms bend their large heads forlornly beside me and I watch as petals slowly fall from them like tears, only moving off when harassed by an intoxicated bee.

July has gone by in a watery blur and my maniacal trudging has been clocked by my smartphone with what feels like mounting concern. I glance at its stats. There it is. I can see my self-torment clearly delineated through the ferocious spike in my daily step count. August is here now; a strange mutant version of it anyway filled with storms and omens and apart from the odd workman and a L-plate car crawling by, there is no one around. Everyone who can has fled. I will too soon enough. Until then, I walk.

Headphones pump a single track into me as I do: a deep house remix of a Sufi-style Bollywood super hit. The intense devotional power of the gravelly female vocals combined with heavy basslines and distorted otherworldly effects feel like the perfect sublimation of my distress. It is at once heartrending and heart-pounding; Eastern and Western; ancient and contemporary. I listen to it on loop. One song replayed a thousand times. If that sounds mad, then that would be spot on.

As I walk, it occurs to me that I am not asking myself the right questions. Perhaps it’s not so much how I failed, but why?

Raining Sushi

It is well known within my family that no Valentine’s Day celebration can ever come close to the one I once spent with Sumeet. It was 1999 and the two of us singletons had clearly decided that this annual day of torture was best endured together through an anti-celebration. I recall each of us making multiple calls on the day to secure a restaurant reservation, predictably to no avail. When we finally admitted defeat, it’s fair to say that we were both seriously peeved with the selfishness of romance.

We switched to Plan B. I would go over to Sumeet’s 3rd floor flat in Notting Hill and he would order in sushi while I would bring the bubbles. Upon arriving, I could tell he had given vent to his frustrations because I had never seen that amount of sushi before, or indeed, since. Large trays of raw fish covered his entire dining table, too much to possibly eat, while I, in turn, had turned up with not one bottle of prosecco but two. We valiantly did our best to drink them both at which point, things took an increasingly surreal twist.

As we noticed loved up couples wandering past from Sumeet’s window, presumably on their way to the very dinner reservations that the two of us had been denied, it is highly possible that we began to jeer from our elevated vantage point before quickly ducking from sight in fits of giggles. It is also possible that projectiles of uneaten California rolls and Salmon Nigiris began flying through the air, landing with soft flumps on the pavement below. I couldn’t possibly comment.

All I can attest to is that whatever went down, the pair of us repeatedly fell on the floor and laughed like crazed toddlers. As I said, both ridiculously juvenile.

Love, Life and Gratitude

A few years later and the two of us no longer needed to mock the concept of love for we had both found it. In Tamawa, a serenely beautiful woman who was every bit as much of a smarty pants as Sumeet, it was obvious to everyone that he had met his soulmate. Their three-day wedding extravaganza in New Delhi was magical and I was thrilled to be part of it. In turn, the two of them attended my wedding in Provence where Sumeet memorably kicked off the disco by grooving to a medley of Michael Jackson hits.

Children followed for each of us, these gorgeous little things, and our social lives contracted to adjust. Sumeet’s journalism career had now gone stratospheric while I had begun writing a novel. We made sure to still see each other for the big celebrations along with the odd dinner, but midlife is brutal and there’s no doubt that the daily obligations of parenthood combined with the additional pressure of elderly (and in my case, dying) parents as well as the reality of not living close by each other affected our ability to stay in touch as much as we would have liked.

And then the Pandemic arrived, and all our lives telescoped further. I was devastated to learn in its early days that Sumeet had been diagnosed with the Big C. Sitting on a cold park bench during the solitary hour we were permitted to spend outside, I cried down the telephone to him, scared witless of what lay ahead. But with Tamawa’s unwavering support, Sumeet was able to not only endure but overcome every challenge thrown his way with his characteristic humour and courage. Life had changed irrevocably for him, without doubt, but he was still around and that’s all that mattered.

Last June, Sumeet and I made the painful decision that he shouldn’t attend my birthday celebrations due to the health risks of attending a large gathering. Instead, my family and I travelled to the other side of London a few weeks later to celebrate with his family at their place. It was one of those glorious midsummer luncheons where the conversation flowed, the kids bounced dreamily on trampolines (when they couldn’t steal our phones), and the laughter rang out so loud and clear that if I shut my eyes, I can almost still hear it today.

And yet, the memory gives me pause. There is something not quite right about it and I frown as I dig around until finally a razor-sharp splinter embedded deep within my psyche works its way out. Before lunch. When I was helping Sumeet finish up in the kitchen. When his wife was upstairs dealing with their kids. When my husband was in the living room dealing with our son. The moment that Sumeet confided in me that he was having small doses of treatment again just as a preventative measure and when I grew upset, hastening to reassure me that he was fine. Just fine. No need for worry. No need to be scared.

Him reassuring me.

My frown deepens. Why hadn’t I pushed him like I would push a reluctant interviewee? Why hadn’t I sensed I was not being told the full story? Why had I seized on his words of comfort with such relief? After weeks spent walking in circles for literally hundreds of miles, an answer floats up like seaweed in the tidal churn that comes after a great storm.

This year, the festival of Raksha Bandhan has fallen on the 30th of August and it finds me sitting tearfully in a hotel lobby in Barcelona. I scroll through old messages from Sumeet. I will never ever get another from him playfully demanding to know where his rakhi is. The sense of loss is overpowering not just for myself but for his wife, his kids, his mother, his friends and his colleagues; in fact, every single person deprived from here on in of his singular presence; but I am also aware of something new emerging on its peripheries – gratitude; gratitudethatI was lucky enough to know this extraordinary man; gratitude that he asked me to call him brother.

Once upon a time, long, long ago, Sumeet made a promise to protect me, and I choose to believe, that in his own way this is what he did right until the very end.

A STRANGER recently emailed me in a state of distress. She had been on a spiritual journey, she wrote, but all her beliefs were now at risk having watched one of my documentaries. The experience had left her shattered, and she asked if she could put some urgent questions to me. This heartfelt request, sent a few minutes after midnight on a Saturday, was chased by another one sent just before six am on the Sunday. It was clear to me that only one of us had been sleeping in the interim. Her tone was desperate, and even though I didn’t know her, all too familiar.

Nineteen years ago, I made a TV documentary investigating allegations of sexual abuse and murder against the Indian spiritual guru, Sai Baba, the most powerful godman of his day who commanded some 30 million followers globally. The film entitled Secret Swami went out on BBC2 in the U.K. but also aired internationally via BBC World. The moment it hit the airwaves, it unleashed a storm. Protests immediately broke out in countries with large Indian diaspora communities such as Britain, Canada, Australia, Fiji, Mauritius, South Africa and Trinidad as well as in Sri Lanka, home to a high number of Sai Baba devotees.

It was also the moment that The Emails started.

Row of Crows

Hundreds of them. Perhaps thousands. The truth is, I never counted. All I knew is that they would be waiting in my inbox every day I turned up for work like a row of crows balefully regarding me. Thankfully, most of the feedback was positive and appreciative. A high proportion also contained troubling revelations of further abuse within the Sai Baba community as well as in other spiritual sects. At the same time, there was a significant minority that was highly critical and upset, plus a tiny subsection which was intentionally offensive, laden with bile and ill wishes. And then there were the death threats.

Nowadays, death threats are two a penny on social media, venomously dished out by keyboard warriors hiding behind a mask of anonymity but back in the early Noughties, not so much. The problem was, I didn’t know what each email had in store for me until I opened it. Of course, by then, it was often too late.

Trying to emulate my childhood heroes, JR Tolkien and CS Lewis, who famously penned replies to their legions of fans, I stoically made it my duty to answer every single email even the negative ones, although needless to say not the ones containing insults or death threats. Email was in its infancy back then and inboxes weren’t as rammed with junk mail or commercial subscriptions as they are today. An email still had a certain cachet; not quite a letter but almost.

Moreover, there was a tone to much of the correspondence that moved me. Leaving aside the straight-out expressions of appreciation or criticism, the rest were mostly written by people who had been or still were Sai Baba followers or in other spiritual communities. There was therefore, a deeply emotional register to these emails, which occasionally veered into distress or desperation, because of how the documentary had affected them personally. Many contained either moving pleas for me to investigate other abusive situations or passionate requests for me to reconsider my investigation based on proof of Sai Baba’s saintliness. No matter what, I respected their courage for reaching out to me. I also felt a sense of responsibility.

A few years down the line, though, and dealing with all those feelings was getting harder. Those ominous crows which showed up every morning had thinned down, sure, but they had far from disappeared from my life. I was still receiving a minimum of two to three emails per week about my Sai Baba documentary despite making numerous other programmes since. What’s more, after a scheduling decision back in 2004 to air the film in India around 3am had led to it being seen by virtually no one, word had clearly got out and the film was posted several times on YouTube unleashing a new stream of emails – as well as a new flood of pent-up emotions – from India, home to Sai Baba himself.

As a new wave of people wrote to me with the immediacy of having seen this film for the first time despite it airing on mainstream TV years earlier, I could deny it no longer. The emails were choking me.

Hard Decision

And so, in 2009 – a full five years after Secret Swami had first broadcast – I made the hard decision to stop responding to any further correspondence about it. I felt justified in this. I had left the BBC and was about to go back to university in preparation for a new career as a writer. I resolved to still read every single email I received out of respect, but to no longer answer as a rule, only as an exception.

Instead, I created a folder within the inbox of my non-BBC email. When the crows turned up, which they still did albeit in dwindling numbers, I simply stuffed them all in there. In my mind, the folder grew into the bottom drawer of a metal filing cabinet, one in which all those crows were still alive, their wings beating and flapping violently in a black whir of distress.

I had no desire to pull that drawer open anytime soon.

And for more than a decade I didn’t. In that timespan, the black crows dropped down to barely a handful each year and I got on with my life.

And then The Stranger got in touch.

Cautious Conversation

When her two emails landed in my inbox in rapid succession, my first response was to freeze. I found the feverishness of her response to my almost 20-year-old documentary disconcerting. Carefully placing the two quivering black crows into their virtual pen conferred instant relief. It was, therefore, irritating to feel a long dormant sense of responsibility bubble back into life over the next few days. Once again, I began to grudgingly appreciate the courage it must have taken for her to write to me. And so, I checked out the stranger’s bonafides online (investigative habits die hard) and once verified, took the two black crows out of their cage, re-read them and cautiously replied. I was sorry to hear she’d been so shaken and although busy, would be happy to answer a few key questions.

The questions that arrived were innocent and unguarded. I was moved by The Stranger’s credulity towards the world, her anguish upon finding the purity of Sai Baba possibly tarnished, and her earnest desire to find out the truth. I endeavoured to make my responses as tactful as possible, employing studiously neutral language to do so.

I described how there had been rumours circulating for years about Sai Baba’s sexual predations and the difficulty of having hard evidence in historical sexual abuse, having to rely on the patterns that emerged instead in the testimonies of victims. I talked about the other Indian males with family members still in Sai Baba’s ashram who I had interviewed about their own experiences of abuse but who hadn’t been included in the final cut because of their wish for anonymity; I emphasised how the suffering was made worse by the fact that many felt complicit in their own abuse through the exploitation of their belief in their guru’s divinity. And lastly, I talked about how it was entirely possible that Sai Baba was both a sexual abuser and a humanitarian; the two did not necessarily negate the other; and I gave her examples of public figures who had gone on to be unveiled as sexual predators.

Lastly, I wished her luck making her mind up based on her own instincts.

Do Facts Even Matter?

Did I think that she might come round to believing that Sai Baba had secretly preyed on adolescent and young male devotees while also performing vast feats of philanthropy for society’s most needy? Potentially. But I am not so naïve as to take that for granted anymore. Nineteen years ago when I was a gung-ho foreign correspondent, I genuinely believed that my BBC investigation would lead to most of Sai Baba’s followers abandoning him, but that clearly didn’t happen even if it benefitted countless individuals as evidenced by the majority of my emails.

Why? One reason is that neurologically, beliefs are extremely hard to change. According to the article, Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds And Beliefs Are So Hard to Change, by Imed Bouchrika on the website www.research.com, scientists have discovered that sticking to one’s beliefs actually activates the brain’s pleasure centre. In other words, we are genetically designed to feel good about standing firm when our views are challenged.

Bouchrika also names a phenomenon called belief perseverance, which “refers to people’s tendencies to hold on to their initial beliefs even after they receive new information that contradicts or disaffirms the basis for those beliefs.” Confirmation bias, a person’s tendency toreject information that does not confirm their views or prejudices, may also play a big role in stopping people from seeing things objectively, he writes, and provide “justifications for decisions one has already made.”

And naturally, over the course of almost two decades I have also changed within myself. Human beings are not monoliths, we learn and evolve through our experience of living. These days, I practice Kundalini Yoga, an ancient yoga practice rooted in Shaktism and Tantric Yoga that dates to eighth century India. My fellow practitioners are some of the warmest, most spiritually curious people I’ve ever met and our WhatsApp group often pings with the diverse mystical interests they are pursuing, some of which I’ve never even heard of.

While the practice of Kundalini Yoga is more than enough for my needs, I have come to understand that there are increasing numbers of people these days who are engaged on spiritual quests to help them process past trauma or help guide them through the challenges of modern life or simply make sense of it, and in realising this, I have grown into a more compassionate and tolerant person.

Acceptance of Difference

After a short and pleasant correspondence, The Stranger eventually replied to tell me of her decision. Sai Baba was her guru, she wrote, because he had helped her to overcome her inner darkness and her joy in volunteering came from his teachings. She had, therefore, decided to forgive Sai Baba in favour of the good deeds he had done for millions of people while accepting that she would never know the ultimate truth to the allegations against him. With that out of the way, she now worried about the youngsters who followed Sai Baba coming across my documentary on YouTube and being guided back to the path of darkness and misery. Would I help her to take it down?

The request made me smile. I had clearly done a very good job of coming across as neutral!

I wrote back to tell her that I was pleased she had resolved her confusion but that she might have misunderstood my position. I still stood by my investigation. As for taking down my documentary, I’d had nothing to do with putting it up in the first place. Instead, I emphasised how in an increasingly polarised world, it was vitally important to tolerate people with different views without attempting to silence them. So just as she would have to tolerate people who had accused her beloved guru of sexual abuse, they would have to tolerate devotees like herself who chose to ignore their harrowing stories. As Voltaire put it so well, “Tolerance has never provoked a civil war; intolerance has covered the Earth in carnage.”

And with that, I felt the black crows lift into the air and soar away.

Forcing myself to converse with The Stranger after all these years about a subject I had avoided for so long had inadvertently released me from its psychological control and I am grateful for her intervention. Thanks to her, I finally delved into the folder that I could barely look at before, even reading some of the oldest emails stored in there and guess what? I no longer felt suffocated by all the desperation and distress they contained. I was free.

Once upon a time, I made a documentary that slammed into the ground like a meteorite because it dared to tackle that most precious of things – people’s beliefs – and the repercussions from that impact lasted for years and still continue today. But I don’t regret it. It was important to investigate those allegations. Whether you choose to believe what I discovered is up to you, though. Take responsibility for your own beliefs.

© Tanya Datta

DYSTOPIAS make gripping settings for science fiction novels. That’s how I first learned about them as a teenager. There was the despotic superstate Oceania in George Orwell’s 1984; the brutal theocracy of Gilead in The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood; the paranoid Galactic Empire in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation; and the savagely feudal Imperium in Frank Herbert’s Dune.

These enthralling books, alongside others that I eagerly gobbled up in the mid to late 1980s, might have been set in a variety of disturbing post-apocalyptic and futuristic societies, but they all had one reassuring factor in common: they were fictional. As such, each imaginary dystopia functioned for me as a parable. A literal warning of what could happen if our society lost the plot.

Of course, I was aware of real-life dystopias, but as far as I could tell that kind of extreme societal misery was consigned to the history books, orotherwise unfolding safely elsewhere. Here in Blighty, we had our fair share of injustice and heartless policies without doubt, but for the most part I believed our nation – leaving aside its dark imperialist past – to be a relatively benign one. A place where democratic processes still worked, and it remained possible to express dissenting opinions.

I am no longer so sure of that anymore. Chilling developments in recent years have shot great gaping holes in my blanket assumption of our overall societal wellbeing and I don’t think they can be easily patched up.

Food Banks and Warms Rooms

We now live in an era of Food Banks and Warms Rooms. A time when a thousand people in England can die from the cold in the month of December alone, while a few months later oil and energy companies announce record profits running into billions. A period in which one in five of the UK population officially live in poverty forcing millions of vulnerable households into an existential choice between heating or eating as our nation grapples with a cost of living crisis that has seen the prices of everyday essential items rocket and energy bills nearly double within a year.

Last year’s summer of discontent has accordingly swelled into this year’s tsunami of industrial action leaving society in frequent paralysis as unprecedented numbers of public sector workers have walked out en masse to protest over their pay not keeping pace with inflation. It includes the biggest NHS strikes in its history only two years after Britons regularly applauded NHS staff alongside other essential workers for labouring selflessly through the pandemic.

And how has the British government responded to this societal cri de coeur?

By passing hard-hitting laws to limit the impact of such protests, that’s how. They range from the Strikes Bill, which enables minimum service levels to be safeguarded in key sectors during periods of strike action, to the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act as well as the Public Order Bill, the last of which came into force just days before the Coronation and was used to arrest several anti-monarchy campaigners on the day itself and hold them for up to 16 hours without charges – a heavy-handed response to peaceful protestors not often seen on these shores.

It would be one thing if inflationary pressures were affecting everyone proportionately, but income inequality in the UK, already one of the highest in Europe (with a Gini coefficient ranking it as worse than Romania), is on the rise. Runaway executive pay and excessive shareholder returns are deepening this chasm. Plus the inadequacy of current welfare benefits to cover minimum living costs has led to an explosion in destitution.

Health disparities between the South East and the North are also widening. In wealthier areas, life expectancy is now nearly 15 years higher, which is almost the same gap as the UK average and Sudan. In short, the UK is growing sicker and poorer.

Welcome to Britain’s Inequality Games!

Obscene Disparities

If I sound downcast, it’s because I am. Our country today is one of obscene disparities. A polarised nation that lurches from crisis to crisis, never properly resolving anything and leaving its people feeling helpless, disillusioned and lied to. A dystopian society – yes, I’m calling it – in which the number of children in food poverty almost doubled in the past year to just short of four million while in the same period the combined wealth of all UK billionaires went up too.

All of which finds me sitting opposite a man with an idea.

Phillip Ullmann, a social business entrepreneur who once ran the UK’s leading talents solutions group with a combined workforce of 100,000, might not look particularly radical at first glance with his navy blue suit and neat silvery hair capped by a kippah, but his vision of creating a fairer society through utilising an ancient form of pledge called covenant is nothing short of revolutionary.

It’s why I have come to meet him – hope being such a rare elixir these days – despite this subject falling outside my usual journalistic beat.

It is strikingly apt for someone who cites religious concepts regularly that it was an epiphany which upended Phillip’s traditional career path a few years ago. As CEO of the Cordaunt Group with revenues at its peak of more than £1.2 billion, the realisation that business, specifically the pursuit of making money, wasn’t fulfilling him hit him hard and he began to cast around for what business could be about. When he came across the concept of social enterprise, he was hooked.

Here was a “a completely different way of operating where your purpose is not looking after yourself or a group of shareholders. You’re focused on people… the planet… a much wider range of stakeholders.”

His attempt to bring Cordaunt along with him on his journey towards greater social purpose, however, was more challenging than he had anticipated. In 2020, Cordaunt went into administration before being bought up and rebranded into a new business. It was a salutary lesson, Phillip acknowledges; one that taught him that if the objective of making money for shareholders is embedded within a company’s DNA, it is almost impossible to change that organisation from within, nor is it even fair.

Ancient Concept of Covenant

Phillip was not to be deterred from his path. Three years ago, he began to study the Hebrew Bible with a circle of Biblical scholars during lockdown, a development he wryly concedes as “crazy” and it was this close reading of it coupled with his unfailing eye for business that was to lead to his most revelatory insight yet; namely that the ancient concept of covenant, a form of pact common in early near Eastern societies involving promises made between different parties based on a desire to work towards a common good, was still fit for purpose and relevant for the modern age.

Covenants, he believes, offer “real and pragmatic” solutions to the inequalities and exploitative practices that result from our current business models which are overwhelmingly contractual. Covenants mean delivering for stakeholders, not just shareholders. And he’s practicing what he preaches. Today, he’s the CEO of the Covenant Advisory, a consultancy “building business coalitions and linking these to state and civic institutions.” Remodelling society around a kinder, more inclusive covenantal approach, he is convinced, really can change the world.

Now I’d be the first to admit that turning to a pledge framework that dates back several millennia as the answer for our current economic woes sounds fantastical. But I’m also intrigued. How can a construct birthed in such a spiritual era have traction in our modern, decidedly less devout times?

The answer, according to Phillip, is that it’s already alive and kicking in the estate of marriage which, although still a legally binding contract, works on a far deeper level because of the promise two people make to each other. In other words, a good marriage succeeds because the interests of both parties are aligned in a higher purpose than they would be in a transactional exchange in which a seller tries to sell something at the highest price and a buyer wishes to purchase it for the cheapest price causing the interests to be misaligned.

“You’re not competing with your wife, you’re trying to achieve things together that you can’t achieve separately,” he says. “Having children, building up a loving family, working as part of a community. So, it’s about collaboration, working together in a loving relationship… moving from a completely competitive ruthless environment where it’s survival of the fittest to a world where we actually care for each other; we care for the eco-system.”

There is much to unpack in Phillip’s thinking about how we can revitalise our dysfunctional economy through covenant. Some of his theories are already fine-tuned, others less so. But as the cogs of my brain whir to keep up, I notice myself growing energised by our discussion of fairer, more accountable methods of doing things in a way that I haven’t felt in years. Most of my prepared questions fall by the wayside. Instead, I listen, really listen, and respond with genuine curiosity.

By the end of our conversation, I think I understand that a covenant seeks to foster relationships between people, even ones with estranged interests, to join together for our common good. And it’s this – our relationships with our family, our community and our land – that is the key driver of human endeavour, not money. Once we look after those fundamentals, the payback is on a whole different level.

Is such a covenantal future possible for the UK? I don’t know. It feels a little like a utopian dream but perhaps the depressing realities that our country is enmeshed in today have caused my imagination to grow smaller and gloomier. What I do know is that we all need to be having a big conversation about what we want to be as a society going forward because it’s never been more vital and a covenantal approach should be absolutely on the table.

© Tanya Datta